While developing machine learning (ML) algorithms in production environments, we usually optimize a function or a loss that has nothing to do with our business goals. We generally care about metrics such as click-through-rate or diversity or ad-revenue but our machine learning algorithms often minimize log-loss or root mean squared error (RMSE) of arbitrary quantities for computational ease. It is often seen that these ML metrics don’t correlate with the original targets, which is why running online A/B tests is so vital in production because it lets us verify our ML models against the true objectives of a task.

However, running A/B tests is expensive because it requires some productionized version of an experiment, which needs to run for a significant amount of time to get reliable results during which you risk potentially exposing a poorer system to the users. This is why reliable offline evaluation is absolutely critical – it encourages more experimentations in a sandbox environment as well as help in gaining intuitions on what is worth launching/testing in the wild.

Classic offline evaluation of user-interactive systems

A user-interactive system (e.g. product search, social media feeds, news recommendation etc.) involves showing a user a set of items given a certain user context or intent. In such systems, users can only click/like/dislike the items recommended by the system. A classic information retrieval way to evaluate how good such a system performs offline would be something akin to mean average precision (MAP) or normalized discounted cumulative gain (NDCG) where you store historical user interactions, and validate your system by verifying whether the algorithm places the items a user interacted with at the top of the recommendations.

While it has been common practice to evaluate systems using these kinds of approaches, it is often observed that optimizing such metrics don’t necessarily correlate with the business KPIs. There are a few reasons why this discrepancy exists, and one of the biggest ones is the huge presentation and sampling bias that exists in the user feedback logs on which offline evaluation metrics are calculated. Given the nature of the systems, it is problematic to evaluate newer algorithms that may recommend items that were never shown to the user in the first place and evaluating on aggregate data can result in confounding results.

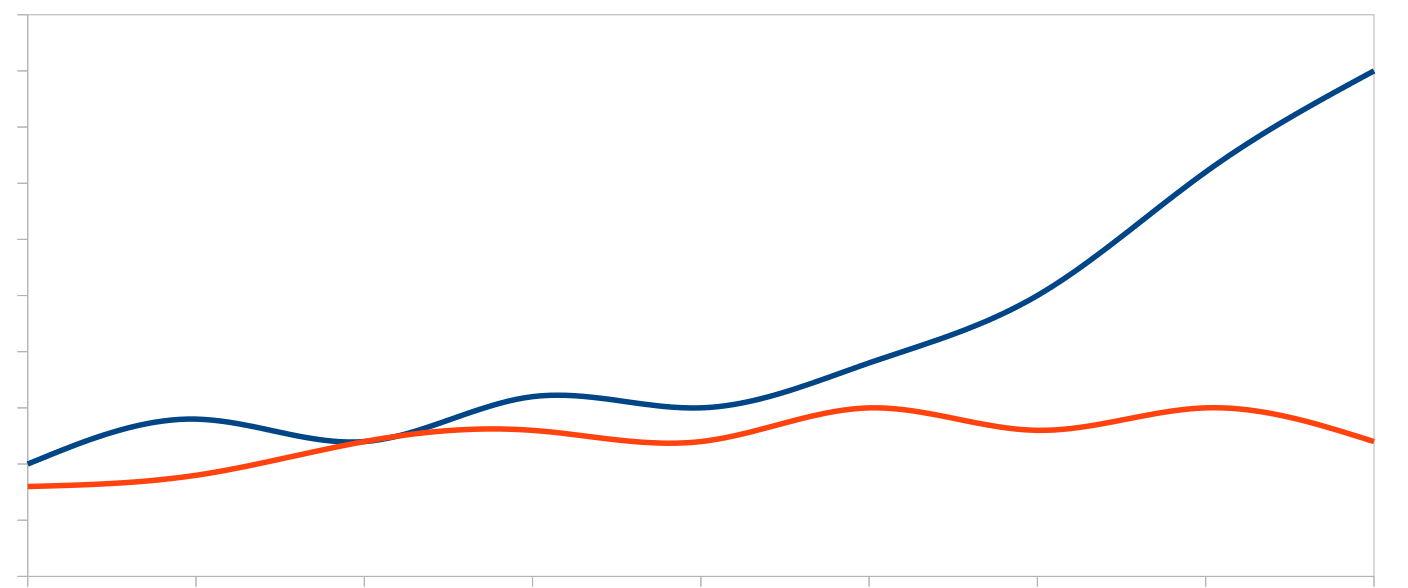

For example, imagine in a news recommendation problem, you were trying to evaluate two algorithms that performed differently for two different kinds of content (major publication and long-tail). On first glance, it may be obvious to say that Algorithm 2 is probably “better” than Algorithm 1 but in industry it is often the case that you can have Algorithm 1 running in production, and you may have realized that it performs poorly for long-tail content and hence mostly only recommended articles from the major publications, and wildly overestimate the true performance of an algorithm.

| Major Publishers | Long-tail | |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm 1 | 0.80 | 0.20 |

| Algorithm 2 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

Had the users been exposed to the true distribution of major publications and long tail content by our algorithm in production, we could fairly evaluate our algorithms offline. To mitigate presentation bias, we can always pick a small fraction of users that are always shown uniformly random results and the feedback we observe on these results would not have the same sampling bias of the existing algorithm in production. This can obviously be an extremely hard sell to any business/product to show some users completely bogus results. Since showing uniformly random results is mostly impractical (some companies have nevertheless succeeded in doing so), this post explores alternative possibilities for offline evaluation using counterfactual thinking.

Offline evaluation as a regression problem

In user-interactive systems, it is generally easy to collect a dataset ( \mathcal{D} = [(x_1, y_1, r_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n, r_n)]) where the \(x_i\) is what a system knows about the user and their intent, \(y_i\) is the item recommended to user by some “algorithm” \(\mathcal{A_0}\), and \(r_i\) is the reward (like/view/dislike) that a user provides to the system. This reward can be both implicit (view) or explicit (upvote). Many recommendation algorithms such as collaborative filtering use this dataset to learn algorithms that can generate better \(\textbf{y}\). In contrast, an offline estimator’s goal is to estimate the rewards \(\hat{\textbf{r}}\) given a new set of \(\textbf{y}\) generated by a different algorithm \(\mathcal{A}\).

Given this dataset, it is relatively straightforward to learn a reward predictor \(\hat{\textbf{r}}\) as a function of the user-context and the recommended items if we think of the offline estimation problem as a classic linear/ridge regression problem.

\[min_{\textbf{w}} = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^n (\hat{\textbf{r}}(x_i, y_i, \textbf{w}) - r_i)^2 + \frac{\lambda}{2} \left\lVert w\right\rVert^2\]Unfortunately, this doesn’t work very well because the sampling bias in our data plays a huge role, and even with heavy regularization, the reward predictor is generally found to be not very indicative of true evaluations.

Modeling the reward as a function of these two inputs can be problematic as it introduces modeling bias. User feedback can have external reasons outside of what the dataset captures; for example, a user may choose to ignore a long-read news recommendation while queueing for coffee at a cafe but may have loved the recommendation in other uncaptured contexts.

Counterfactual Thinking

Another reason why a vanilla reward predictor doesn’t perform that well is because offline evaluation is fundamentally an interventional problem as opposed to observational. We only observe the logged data generated by an algorithm \(A_0\) in production, and we try to estimate what if the users were recommended some other items. There are some intricate differences in observing \(\textbf{y}\) in logs and setting \(\textbf{y}\) to different values (counterfactuals) and trying to estimate the reward. Ferenc Huszár has some really good blog-posts on the intricate differences on this, and I highly recommend checking them out.

Inverse Propensity Scoring

Given a counterfactual framework, modeling the bias in the logs directly as opposed to modeling the reward works much better for offline evaluation. One classic way to do that would be Inverse Propensity Scoring (IPS) which evaluates treatments independent of the logged confounders. The key idea in IPS is to reweight samples based on propensities of the logged items using importance sampling. Propensity \(p_{x_i, y_i}\) in this context is simply the probability of the item \(y_i\) shown to the user \(x_i\) at the point of logging.

If propensities for the live algorithm \(A_0\) were logged, our offline dataset would look more like \(\mathcal{D} = [(x_1, y_1, p_{x_1, y_1}, r_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n, p_{x_n, y_n}, r_n)]\). With this data, IPS gives us unbiased estimates of the performance of any algorithm with:

\[\textbf{Performance}(A) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (r_i \cdot \frac{p'_{x_i, y_i}}{p_{x_i, y_i}})\]Where \(p'_{x_i, y_i}\) is the propensity for \(y_i\) item to be recommended to user \(x_i\) for a new different algorithm \(A\). Because of the nature of the equation, for any item that is recommended by the new algorithm \(A\), \(A_0\) needs to have a non-zero propensity for that item. Here’s some sample Python code that lets you evaluate performance of a new algorithm offline.

def inverse_propensity_scoring(user_feedback, num_items_displayed):

"""Compute Inverse Propensity Scores given user feedback

Parameters:

user_feedback (list): List of tuples of (user_id, item_id, feedback)

feedback is assumed to be something like a `view` or a `like`, and we have associated rewards for them in FEEDBACK_WEIGHT

non-clicks or feedback that is considered to have a 0 weight need not be a part of the list.

num_items_displayed (int): Total number of items displayed to all users (cumulative)

Returns:

float: Estimated click through rate

"""

utility = 0.0

for user_id, item_id, feedback in user_feedback:

# assuming there are functions that return propensities (probabilities) for an item_id and user_id pairs

utility += FEEDBACK_WEIGHT[feedback] * (propensity_experiment(item_id, user_id)) / (propensity_production(item_id, user_id))

return utility / num_items_displayed

Practical Points and Ingredients to make this work

Deterministic Ranking Algorithms

Most user-interactive systems tend to be in full exploitation mode and score a list of items based on content or collaborative (or both) filtering, and then greedily rank/sort before showing them to the user. For IPS to work, however, the system needs to be stochastic and many production systems don’t run such stochastic algorithms. The propensity_production function in the code snippet above in a deterministic algorithm is always 1, and as such it doesn’t supply the required information.

A practical way around it is to get multinomial samples without replacement, i.e. create a weighted dice based on the scores and roll for each item, reweighting the dice after each roll. If we have a score for each (user_id, item_id) tuple, then we can simply use NumPy’s np.random.choice with replace=False. This is sometimes also referred to as Plackett-Luce method and the main selling point of this solution is that the mode of this multinomial is the reverse sorted deterministic function.

Non-zero propensities for items

Generating propensity for every item for many problems such as news recommendation is almost impossible given the number of articles that get published on the internet everyday. Practically, if the feed length was 50 for each user, we could simply create a multinomial of the top 500 items or so for each user under the production algorithm \(A_0\) – this means that we won’t be able to evaluate a future algorithm \(A\) if it were to recommend items outside of this candidate set to the user but if the algorithm in production was any good, the top 500 items would surely include the best 50 of a better algorithm.

Potential Improvements - IPS has High Variance and High Sampling Complexity

While IPS lets your evaluator converge to the real performance in the limit, it is still an extremely sample hungry algorithm (requires a lot of logs) and the estimates can have high variance with few samples. If you have bucket loads of logs, then it is probably not a problem but Adith Swaminathan and Thorsten Joachims have developed a better normalization for the problem, which makes IPS a little less sample hungry and is evaluated by:

\[\textbf{Performance}_{\textbf{(SNIPS)}}(A) = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n (r_i \cdot \frac{p'_{x_i, y_i}}{p_{x_i, y_i}})}{\sum_{i=1}^n \frac{p'_{x_i, y_i}}{p_{x_i, y_i}}}\]def snips_scoring(user_feedback):

"""Compute Inverse Propensity Scores given user feedback

Parameters:

user_feedback (list): List of tuples of (user_id, item_id, feedback)

feedback contains all usage such as `non-click`, `click`, `like` etc., and we have associated rewards for them in FEEDBACK_WEIGHT

non-clicks need to be a part of the list.

Returns:

float: Estimated click through rate

"""

utility, denominator = 0.0, 0.0

for user_id, item_id, feedback in user_feedback:

# assuming there are functions that return propensities (probabilities) for an item_id and user_id pairs

propensity_ratio = (propensity_experiment(item_id, user_id)) / (propensity_production(item_id, user_id))

utility += FEEDBACK_WEIGHT[feedback] * propensity_ratio

denominator += propensity_ratio

return utility / denominator

Note that in Vanilla IPS, to estimate something like a click-through-rate properly, we could simply look at a look at the clicks (assuming the FEEDBACK_WEIGHT for a non-click is 0), and accumulate our utility, but in SNIPS, the normalization (denominator) needs to be accumulated over all feedback. Unless you are working with a perfect system where most recommended items are clicked on, this requires a massive increased storage of logged usage events but the utility converges much faster. You can’t have your cake and eat it too.

Finishing Thoughts

Evaluating A/B tests offline can be an extremely underrated tool to have for any business. These methods have been quite successful to evaluate “ideas” offline at many companies such as Yahoo, Microsoft, Netflix and Pandora, based on the REVEAL workshop at RecSys 2018.

One thing to note is that this post mostly focused on per-item rewards such as click-through, but it is also possible to model per-feed rewards such as session time-spent but it gets a bit tricky because of the many combinatorial possibilities of the items in each feed. There has been some recent work called the Slates evaluator that deals with this exact problem, which I am hoping to write about in a future post.